Do books make money?

16 July 2025

Photo by Craig Stephen

Photo by Craig StephenAward-winning Perthshire author on the ‘business’ of books

The numbers don’t lie.

If you look at the business of books today, you see, boom.

In 2024, UK book market revenue was £7.2 billion. Fiction was up 18%. Audio books rocketed 31%. Digital soared by 17%.

Only non-fiction was down (4%) to £1.1 billion.

In 2022, The Publishers Association reported the highest sale of physical books in Britain, ever – 669 million.

That’s a lot of ink and, encouragingly, for those with a dream of making it as a novelist, a tangible indicator that appetite for the written word remains robust.

However, numbers rarely tell all the story, all the time.

What the publishing industry grosses often looks very different from the bank accounts of the thousands of UK writers greasing the sector’s wheels with new narrative arcs and memorable characters.

Between the lines

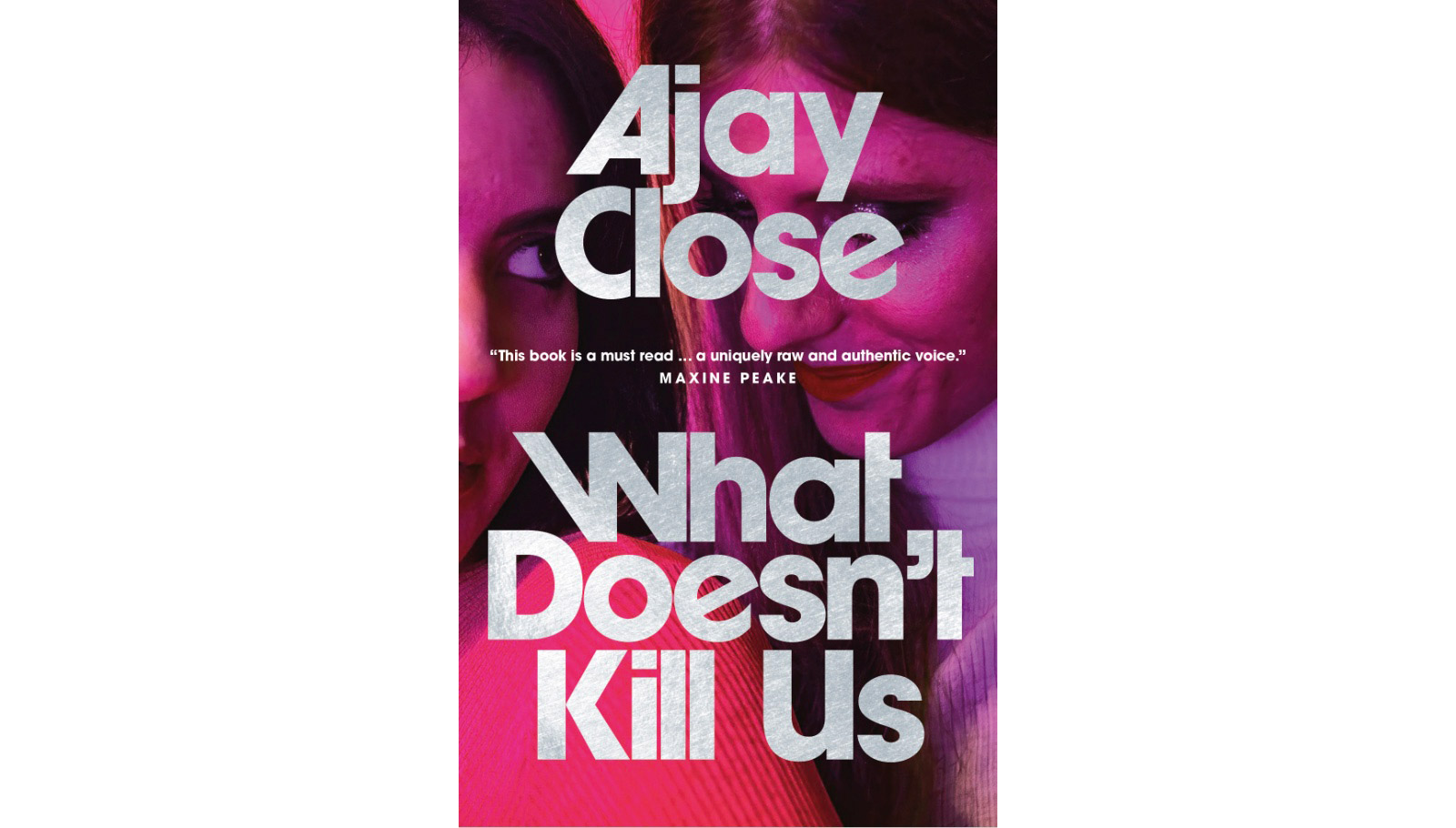

Perthshire Business News was privileged to meet with one of the region’s finest contemporary wordsmiths, award winning author Ajay Close, to establish the context around the business of books.

Her most recent work, What Doesn’t Kill Us, was crowned Fiction Book of the Year 2024 at Scotland’s National Book Awards in December, although she is no stranger to prize longlists.

Ajay embarked on a full time writing career after working as a Journalist for titles such as Scotland On Sunday and, with 7 books now on the shelves, is well placed to offer insights into how to survive and sustain a living in an industry which she admits is ‘super competitive’.

“I once led one of those Guardian Masterclass writing classes they used to run,” she recalls. “I said to the group: who here lives in London? Then I said to them: you need to leave London. It didn’t go down well,” she says, laughing.

“London is very expensive. It depends how much of the time you want to spend writing and how much of the time you want to spend working for money.” This, in a nutshell, is the crux for many authors taking their first uncertain steps in the profession or even continuing the odyssey.

True, Ian Rankin makes a million every time he sends off a new Rebus manuscript (and six figures in a ‘fallow’ year according to an interview in Edinburgh Evening News) but for every Rankin there are countless hundreds of budding scribes looking for ways to supplement their writing income. Furthermore, the Oxford Bar’s most pictured punter wasn’t always the pay check magnet he is today.

“Ian Rankin came to speak to Johnstone Writers when I was Writer In Residence there and he was fairly low level at that time, maybe in 1998/99. It was just as he was on the cusp of making it big,” Ajay says, recalling that it was not until he wrote Black and Blue, (Rebus Book 8) that he began to stop worrying about the rent.

Photo by Craig Stephen

Photo by Craig StephenBalancing the books

The book business, like many others today, is in constant flux.

In days past, the dream was to pen a novel and net a publisher offering a weighty advance to smooth the path ahead. After that, you could turn your attention to rights, royalties and ringing tills.

“With my first two books, the advance was a low 5 figures, with foreign sales and film options after that. I wouldn’t expect to do that again,” Ajay remembers.

“Advances are much smaller. I have been offered £500 by a big-name London publisher and, to be honest, if you are offered £1000 these days, you are doing quite well.”

So where are the gains to be made and are the are any hacks to being a ‘survivor’ in the new age of publishing?

For Ajay, a former Writer In Residence in Perth and Kinross, the key, ultimately, is to love the craft and the words on the page whilst being alert to opportunities and the quirks that can deliver an edge.

“Rule 1 is to be comfortable and true to yourself,” she says.

“I am never going to be all over X, Facebook and Instagram all the time. If I was, I’d never write a word, so I don’t do it. Ultimately, a good publisher will respect that.

“Obviously, in an ideal world, they’d want you to be picked up by Stephen Fry and go viral but ultimately you are allowed to say, I don’t want to do that.”

This approach comes with trade-offs that Ajay is well aware of but she prefers human connection when it comes to wooing potential customers.

She is a firm believer in things like Women’s Institutes and U3As. The data would suggest she is not wrong. This demographic has spare time, wants to keep their brains active - and they want to read – and buy – books.

“When I was a TV reviewer, there was a documentary about country singers in America way back, people like Willie Nelson, and every night they’d play their songs at different towns. Basically, that is my policy.

“I don’t do a reading every night but if anyone wants me to do anything I say yes, hoping for word of mouth and recognition of my name in the bookshops.”

Festival attractions

Unlike in England, book festivals in Scotland can be a source of additional income to help writers sustain the waves of creativity. These events will, generally, attract a fee in Scotland and are seen as worthwhile opportunities for many writers.

As Ajay says, though, keeping an eye on an angle that can set you apart is wise, both for attracting good publishing deals and prime book festival billings.

“If you have a bit of added value, so much the better. Malachy Tallack’s latest novel is about a guy who writes songs. You can listen to the songs online and I notice he is appearing at the Edinburgh Book Festival this year.

“He has a band with him and they are going to play the songs as well as reading from the book. There have been a number of people who have written novels with recipes attached. Anything that is slightly out of the usual, that will attract attention in national newspapers and on the radio, will sell.

“Also, if it is true and it happened to you then that is an advantage.”

The recent broo-ha-ha over Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path and whether it is the personal tale it has been sold to be, continues to rumble on. However, the basic lesson remains. People love to read personal stories that they can relate to, as Ajay attests. She also believes writing ‘warmly’ is likelier to bring sales success.

Remaining open to potential avenues for film and TV adaptations, too, can be prudent.

Not everyone (in fact, barely anyone) will rival J.K Rowling who, according to Newsweek in 2024, ‘passively’ earns between 50 and 100 million dollars per year from Harry Potter royalties.

However, it can pay to do the research before beginning to tap the keys to Chapter One, with an eye on the big – or small – screen.

“If you were going to be really clued up about it, you would do a lot of research before you chose a subject, preferably one which would be not too expensive to film,” she says.

Photo by Craig Stephen

Photo by Craig StephenStreaming in the new age

New entrants into the wider writing marketplace, such as the streaming channels, have undoubtedly altered the dynamic, providing opportunities for those well placed to exploit them.

However, authors eyeing this throughway should be careful – and well represented – when negotiating that life changing deal, as Ajay explains.

“If you get your book bought by a Netflix style streamer, what they are quite likely to do is buy the rights to your characters. It is not like they will say: this series went down well with the audience, so we want you to write another. They will write their own.

“The intellectual copyright is gone. They can give it to their Writers’ room and tell them to run with it.

“Without a doubt, there is money in that. But if you are a writer, you might think, I want to hold onto these characters. They’re mine!”

*Ajay Close was talking to Perthshire Business News.

Learn more about her work, her books, events and readings at www.ajayclose.co.uk